If Students Can Hack This Course, They’re Ready for Information Age Lawyering

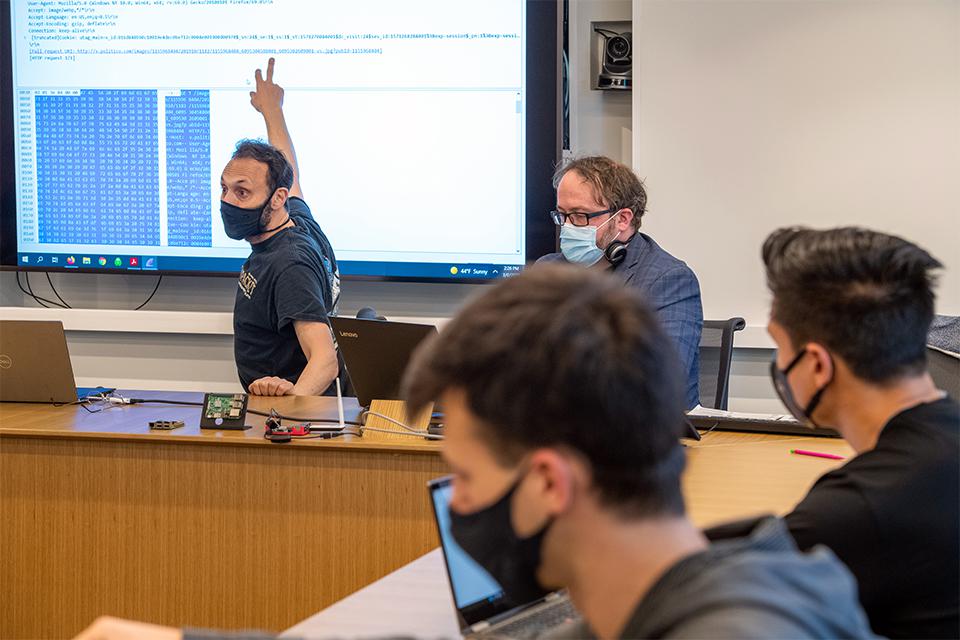

To prepare future lawyers to shape cybersecurity policy, Scott J. Shapiro ’90 doesn’t focus on case law. Instead, the Charles F. Southmayd Professor of Law teaches students how to hack.

Hacking — the act of exploring ways to breach defenses and exploit weaknesses in a computer system or network — may not be part of the conventional law school curriculum. But when students in Shapiro’s cybersecurity course learn how to crack passwords, they see firsthand what it means for devices and systems to be vulnerable to security breaches. With that technical understanding, Shapiro said, they are better qualified to address questions of digital policy, privacy, and national intelligence. And from there, they can make and test laws to protect data from theft and damage.

“The paradox is, we live in an information society and yet we don’t know how it works. The internet is so easy to use, why would you bother learning?”

—Professor Scott J. Shapiro ’90

“It is extraordinarily difficult for law students and for legal scholars such as myself to talk intelligently about regulating an activity that we can’t even imagine,” Shapiro said.

The outline for the course, co-taught by Shapiro and Visiting Lecturer in Law Sean O’Brien, lists topics more often covered in IT classes than in law classrooms. Networks, encryption, firewalls, operating systems, and passwords all appear. However, the course requires no tech skills beyond being able to use a web browser.

Shapiro said it’s a mistake to assume that today’s students — digital natives — automatically understand technology just because they grew up with it. He drew a parallel: few drivers understand the inner workings of their cars. The internet, Shapiro said, is no different.

“The paradox is, we live in an information society and yet we don’t know how it works,” Shapiro said. “The internet is so easy to use, why would you bother learning?”

Shapiro’s first class to examine cybersecurity issues came about after the 2017 publication of his book The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World, which he co-authored with Gerard C. and Bernice Latrobe Smith Professor of International Law Oona Hathaway ’97. The book is about the 1928 attempt by world leaders to make war illegal and the resulting treaty’s legacy on the laws of war. People started to ask Hathaway and Shapiro what the law had to say about cyberwar.

To explore the question, the two teamed up with Joan Feigenbaum, a renowned cryptographer and the Grace Murray Hopper Professor of Computer Science & Economics at Yale, for a class on cyber conflict. The class brought together law and computer science students to learn about the technical and legal aspects of cyberattacks between nation-states. That earlier class informed his current course.

One way the course differs from a typical law school class is that the final project is not a paper but a video of three hacks. One student bought an inexpensive credit card reader and then demonstrated how to hack credit card numbers. Another compiled lists of dictionary words, which people often use in passwords. After putting together a combined list of words that numbered in the millions, the student tested them against a series of obscured passwords — and successfully cracked them.

“We grade not so much on technical sophistication, but on hustle,” Shapiro said.

The class is taught as a lab, in which students learn hands-on. In one exercise, they use one computer to remotely enter another, albeit one that is intentionally buggy and configured for that purpose. Before these activities, students learn the difference between ethical or “white hat” hackers, who use open-source tools to improve and protect the cyber landscape, and people who hack to cause harm. O’Brien said it’s important to distinguish the two.

“Our students need to know how computer networks and data can be breached, and how the humans behind them can be fooled, to truly appreciate the practice of cybersecurity.”

—Visiting Lecturer in Law Sean O’Brien

“With an understanding of this duality, students will finish our curriculum with a respect for the vigilance it takes to protect systems and mitigate or defend against attacks and cybercrime,” O’Brien said. “Our students need to know how computer networks and data can be breached, and how the humans behind them can be fooled, to truly appreciate the practice of cybersecurity.”

Shapiro, who is also a Professor of Philosophy at Yale, has a long history with computing. As a high school student in the 1980s, he got caught up in the wave of personal computing brought in by the Apple II. He learned how to code and before starting law school and completing a Ph.D. in philosophy, he started a company that set up databases. After joining Yale University, he founded the Yale CyberSecurity Lab, which provides cybersecurity and information technology teaching facilities. All the while, Shapiro has been captivated by the legal questions hacking raises. His forthcoming book, Insecurity, details its history, philosophy and technology.

“Hacking is so interesting from a legal perspective because it’s the only activity I know where you can fall within three different areas of the law, depending on who you are and why you are doing it. You can commit a crime, engage in espionage, or start a war. Each of those categories — crime, espionage, and war — are very different from one other,” Shapiro said. “They all have different legal structures. And that’s what, theoretically, really fascinates me about it.”

After Shapiro taught the cyberwarfare class, he wanted to connect with someone with recent experience in the tech world. Through Knight Professor of Constitutional Law and the First Amendment Jack Balkin, the founder of Yale’s Information Society Project, Shapiro met O’Brien, founder of the project’s Privacy Lab initiative. As an IT professional for more than two decades, O’Brien agreed that it’s crucial for future policymakers to have a solid understanding of technology.

“Having a strong knowledge of the underlying tech that intermediates our lives, as well as the security dilemmas, gives the law that governs and regulates that tech vitality and meaning,” O’Brien said. “We don’t want lawyers who believe the internet is just a series of tubes, and we really need lawyers deeply concerned and invested in the strength of our information systems.”

Charlotte Blatt ’22 took the class for just that reason. Blatt, who has a background in national security and foreign policy, came to the class with some sense of the cybersecurity threats facing businesses and governments today. But she said she had little understanding of the issues from a technical standpoint. She wanted to learn more before starting a job after law school at a firm with a data strategy and security practice.

“This class is preparing me for that work because I will be able to better understand what clients are experiencing when they've been hacked,” Blatt said, adding that she’ll be able to communicate with clients “who are facing problems that I previously did not have the words or knowledge to describe accurately.”

Eventually, Blatt hopes to work for the federal government, either as an Assistant United States Attorney or in an agency that deals with national security challenges.

“The knowledge gained from this course is similarly useful when the client is the U.S. government,” she said.

Familiarity with principles of cybersecurity will be crucial for all future lawyers, not just those who will go into that field, Shapiro said. All knowledge workers — of which lawyers are one example — need to protect sensitive information, Shapiro pointed out. For lawyers, that includes their clients’ data. In that sense, cybersecurity is an extension of what law schools have always taught.

“We think of ourselves training the next generation of leaders and, the next generation of leaders needs to know how the internet works. They need to understand how cybersecurity and how hacking works, what the relationship is between hacking, national security law, criminal law, and international law,” Shapiro said. “It’s a vital service for our mission to educate the next generation of leaders for our information society.”